Recently, several acquaintances have asked me how to prepare a “go bag” and it got me thinking. There are many resources out there that offer solid recommendations on what to buy for a disaster and why. Some are disaster-specific (how to prepare for an earthquake versus fires versus a hurricane); others are nonspecific, but focus more on the specific gear rather than a particular situation.

My employer, the American Red Cross, has one of the best overall suite of products for getting yourself and your family ready for some type of natural disaster, and the types of challenges a person can expect to encounter. The U.S. has tools online — for now anyway! — under FEMA, while that agency still has funding. Both of these are useful and make for an interesting if suitably alarming Saturday read.

Meanwhile I thought I’d offer my thoughts about disaster preparedness briefly. Like most people my age (47 as of writing) I’ve had some experience with natural disasters as an adult. I’ve lived through several blizzards, three hurricanes (Gloria, Irene, Sandy), and one high wind event (tornado briefly touched down in my town). I’ve also had experience with war, having helped evacuate my wife’s parents from Kyiv in March of 2022, while Russia was invading, and deployed twice to combat in Afghanistan as an infantry officer.

A brief aside on war: while government resources and the American Red Cross focus on natural disasters and infrastructure disasters such as chemical spills or radiation incidents, nobody talks at length or in detail about the possibility of war in the U.S., or the steps one would need to take to avoid that man-made disaster — a glaring blind spot, though understandable. What government wants its citizens to think war could happen within its borders?

Rather than break disasters into artificial categories such as “natural” and “man-made,” I think a better way to think of disaster prep is “mobile” and “static.” There are some disasters that are fast moving and unpredictable, where one will need to move quickly from one’s home to some predetermined safe area if possible (and in any direction away from the disaster, if not possible). Other disasters are such that sheltering in place and waiting for services such as electricity to be turned on again is the best course of action. In both cases, one will want to approach one’s preparedness for the disaster with a maximum of caution and care.

Here’s a simple way to prepare for disasters of any type using this binary framework.

“Mobile” Disaster Preparedness

I’m beginning with mobile preparedness because one can carry less on one’s person or in a car. For that reason, the kit you build in order to prepare to move in response to or to avoid a disaster must include essential things only; heavily focused on survival for as long as it’s necessary (practically speaking, 5-7 days). Such a kit has to fit in a backpack if you plan to be on foot, or in the back of a car if you have a family and plan to be driving.

It’s also convenient to begin with “mobile” disaster preparedness because you can take everything you put in your “mobile” kit and use it for any other kit you compile.

One can even imagine tiers of mobility, though this is already getting into the weeds (and with disaster preparedness, you really don’t want to get into the weeds — the weeds being survivalism, which is a whole other kettle of tea). There is the mobility which is a few things you can put in your pocket or carry while running. There is the mobility that is a few more things you keep in a backpack and practice using (always practice once a year). Finally, there is the mobility that is stored in the back of your car for your family, requiring no more than two people to lift. Like a nesting doll, the equipment one uses for the first should be part of the second, and the equipment for the second (the backpack) should be part of the third (the car).

Tier One: Mobile Disaster Response With The Clothes On Your Back

This is the most basic disaster response, and any of our ancestors would have understood it. You have to move quickly and for whatever reason using a car isn’t possible or feasible (path you’d take by car is blocked or you don’t have a car, no time to find the keys, etc.); maybe speed is essential and a backpack with 40lbs of equipment will slow you down too much. In this case you want the following:

-Water purifier or water purification tablets + minimum 16oz or 20oz water bottle

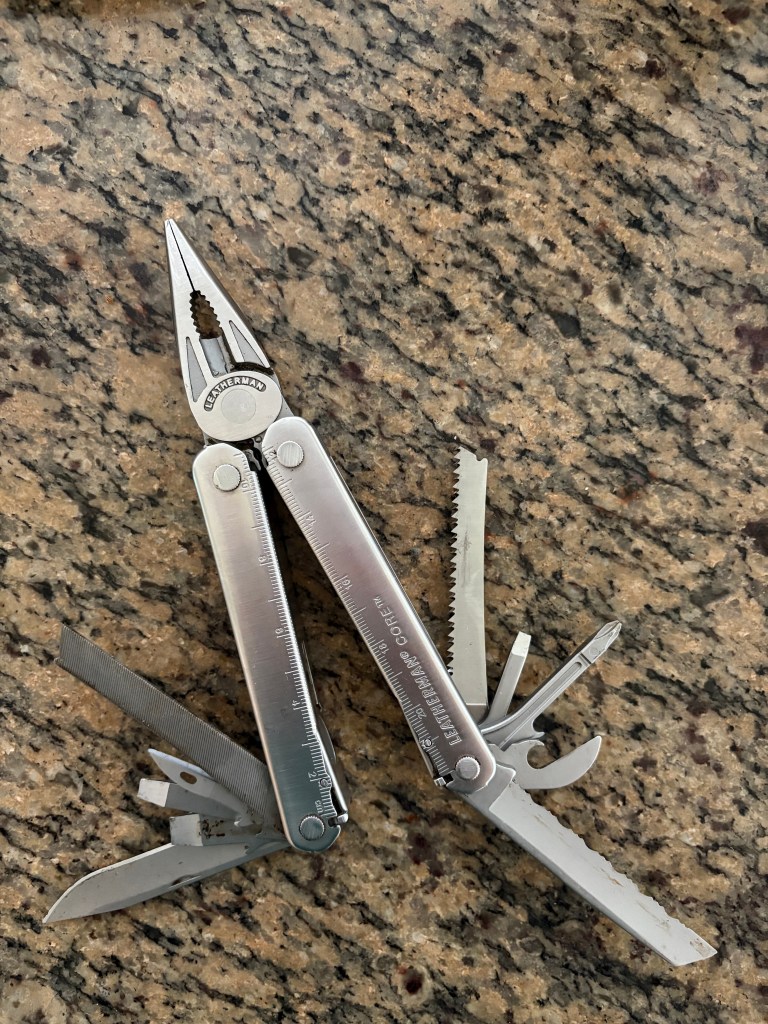

-multitool

-all-weather matches

-rainproof poncho

-plastic baggies

-knowledge of basic fieldcraft

-wallet w/identification; preferably with credit cards and $100 cash, but most importantly with a driver’s license or some other form of valid state-issued identification

Store the essentials of this kit by the front door or back door of your house or apartment, in or next to your poncho. This covers your immediate bases for survival: drinking water being the most urgent. If you know you have access to potable water, you have just bought yourself ~3-4 days of extremely rough living, which is, in almost any situation, enough time to find help for whatever disaster is, presumably, affecting everyone in your area. For clean drinking water you need (1) a water purifier or purification tablets, (2) a way to store the water [the water bottle] and (3) access to any water source. Good water purifiers can clean even the most rancid water source, though it is no way to live for long periods of time. In this case, you are focused on surviving the initial disaster and displacement.

Your multitool — I have an old Leatherman I got before my first deployment to Afghanistan in 2006 and use for household chores — should have a knife, pliers, various screwdrivers, a saw, and some means by which to open metal cans. It can be used to help fashion a crude shelter, start a fire, or do the various little chores one will need to survive outside for a few days.

All weather matches will help you start fires; together with the multitool and some basic fieldcraft, it will be possible to start a fire even in the rain.

A poncho might seem like an odd thing to have hanging up in one’s closet, depending on your cultural background and location; it is an extremely useful piece of kit for surviving under the most austere conditions. Together with your multitool and a few sticks, that poncho can be turned into a waterproof lean-to if it’s wet outside, and a halfway decent improvised sleeping bag if not.

Plastic baggies are to keep things dry — especially your wallet and the matches.

Knowledge of basic fieldcraft, such as how to start a fire, is important for mobile disaster preparedness. Fire will keep you warm, and can sterilize food and (provided you have a suitable container) water. Understanding and practicing building a fire from very little material (dried twigs and small branches and moss) is probably the one essential skill; everything else is a potential nice-to-have.

Finally, a wallet with identification is for when you get to some place that can help you; a safe town the disaster has not reached, a group of people or an organization that’s capable of helping you. A disaster isn’t the end of civilization, it’s just a (one hopes) temporary adjustment in civilization’s borders; a space of temporary lawlessness and disorganization. Your priority is to get back to civilization as quickly as possible and by any means necessary. That $100 will help you do that if the credit cards don’t work, but isn’t so much money that it puts a target on your back.

Tier Two: Mobile Disaster Response With a Backpack

In tier two, one has both the time, presence of mind, and opportunity — and the situation is suitable — to grab a backpack of no more than about 60 pounds; heavy, but not unmanageable for short movements. Such situations could include (1) you don’t have a car but a buddy does and you’re headed somewhere to survive for a week or two, and (2) you’re being evacuated from a place for longer than a week; it’s not clear when you’re going to be able to return though the assumption is that you can return at some point in the future.

Using the principle of “building out capability” I mentioned earlier, everything from the Tier One package goes into the Tier Two package. Thus, you have the first couple pounds of stuff you’ll need to carry.

Things for your backpack that will make some approximation of modern life feasible:

-sleeping bag rated for 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Sleeping bags deteriorate over time, so understand that even a very high quality bag carried by your father since his time in the Guard during Vietnam may not offer the protection it once did.

-If you opted for tablets in the tier one kit over the purifier before, tier two is the time to pull the trigger on a good quality purifier. REI carries a great selection. In general you’ll want something ceramic, capable of purifying spring, stream, or well water. $50-100 will give you peace of mind that nothing bad is making its way into your digestive system. Tablets are ok for a couple days, but you won’t want to be using them for a week.

-frying pan and boiling pot. Boiling water for food, coffee, and drinking will be important (the pot), as will the ability to cook masses of food at once (the pan).

-a mug. If you have to spend a week in the wilderness or something approximating the wilderness you will quickly learn that one of the great challenges facing human civilization is carrying and storing potable drinking water. Creating it is a huge hassle.

-a hatchet. For a week, you will need the ability to create more wood than it is practical to gather by hand, and even then, you’ll be surprised at how long it takes to generate the fuel you need for things like cooking.

-a small hand/hack saw.

-a good steel camp spork.

-two changes of season-appropriate clothes in addition to the clothes you are wearing, stored in a high quality garbage bag or some similar waterproof sack. If planning for a week, you will want to build in a couple days for each article of clothing you have to dry if necessary. The weight of a shirt, pants, underwear (optional) and socks can go from a pound or two for summer wear to a few pounds for winter wear. This shouldn’t take up more than 10 pounds in your bag. Long sleeve shirt and long pants only. Underwear should be moisture wicking / easy dry, whether it’s short or long.

-an extra set of hiking boots or sturdy shoes.

-cash; $500 for emergency use.

-all important documents in a ziplock bag (copy of ssn, birth certificate; passport; driver’s license)

-depending on where you are and plan to be going, a pistol with a couple clips of ammunition

-Two packages (100 count) of wet wipes. This will be sufficient to keep you clean and sanitary for a week. No more needs to be said on that front.

-hygiene kit. For brushing one’s teeth and keeping clean; foot powder if you expect to be walking a lot. Shaving probably not necessary.

-easy-prep food. 21 pounds of this depending on what else you pack. The average person can get by with about 3 pounds of food per day. Unless you’re an experienced woodsman and can augment that food with fish or game, you just need to steel yourself for an uncomfortable week of eating less than you’re used to. If you’re going to a pre-planned location such as a hunting cabin or second home, it’s possible that there will be extra food already stockpiled; this is something you’ll want to figure out beforehand. In any case, bring the minimum of what you’ll need to eat to get by. An emergency is a bad time to discover that someone else forgot to restock a larder.

-external battery, charged. Can give your smartphone an extra couple days of life if you’re using it heavily; if used judiciously, is perfectly sufficient for a week.

-smartphone

-camp stove. I have a MSR Firefly I use when camping that has stood me in good stead. It means keeping a 16oz portable tank or two with propane — but if you’re using it once a year and then cleaning the stove afterwards, you’ll keep it functional and clean, and understand how to use it. This is far more practical than open-fire cooking. Again if you’re heading to a cabin you might end up having access to a stove and more food than you need, or an older fireplace with one of those grill mechanisms (my parents have one of these and use it when the power goes out due to storms or hurricanes, they’re not bad). If you do you may never use the camp stove. Like many of the things in tier two, it obeys the principle of “better to have and not need, than need and not have.”

-two gallons of potable water. That’s 16 pounds. It will give you sufficient water to not die for two days, plus cook some food.

-a set of 5 bungee cords; 4 medium length (2-4 feet) and 1 longer (4 feet+).

-100 feet of 550 or paratrooper cord.

-First aid kit.

Two other considerations are preconditions for this loadout to work with maximum effectiveness. The first is a plan, and the second is, I cannot stress this enough, intermediate fieldcraft. Nobody wants to hear that you have to think through some of this stuff to begin with, but if you’ve thought through the possibility of climate or human disaster to the point where you’ve invested, now, $1500 or so in a durable bugout kit that will give you a week worth of survival outside the comforts of civilization, you really owe yourself the time it takes to ensure that investment isn’t squandered.

The fieldcraft first. That doesn’t just mean unwrapping and assembling the equipment you’ve bought, it means using it. Not field-testing it, using it! Take a Saturday to fire up the camp stove and prepare oatmeal or a soup for lunch. Buy more packaged food than you need and use some of that. See how much water you end up using. Test the purifier. Use the hatchet and saw to practice chopping up smaller pieces of wood. This may take all of several hours per year, a trivial consideration for the knowledge and utility you’ll get out of the process.

Tied to fieldcraft, and together with planning, I recommend joining a nature conservancy or land trust, and taking advantage of the opportunity to learn about where you live. I’m in Connecticut. We have maple tree, and oak, and hickory, and there are ways to prepare the nuts those trees shed in the summer and fall (for this reason I have a small hammer to my field kit, for crushing nuts); acorn and hickory nuts (“pignut” as it’s known colloquially for reasons you can probably guess) can be boiled provided there is sufficient fresh water until they’re not only edible but even tasty. Knowing such things means your 3 pounds of food per day is now 3 ½ or 4 pounds.

With some fieldcraft it becomes practical to develop a plan, either yourself or with friends. Maybe it revolves around someone’s cabin. Maybe it revolves around a camp area, or a piece of wilderness with which you’re familiar. In the case of a natural disaster, a week is a reasonable amount of time to expect institutional mechanisms to kick in — American Red Cross, FEMA, state National Guard, etc. Being out of their way if you don’t expect to contribute anything to the response will help responders deliver help more effectively to people who need it. Paradoxically it may be easier to get to potable drinking water in upstate New York than it is in New Hampshire in the wake of heavy flooding. Heading down to San Diego or up to the San Francisco area from Los Angeles during the fires, if possible, helped firefighters manage and respond to the crisis.

Tier Three: Mobile Disaster Response With a Vehicle

With some disasters, a week isn’t enough, but one still hopes to return home. As with tiers one and two, tier three includes all of the equipment listed in the first two tiers. It also requires a plan that accommodates the length of time you plan to be displaced from your home, and the equipment you’re bringing, including the car. If you have an electric car, planning will be more complicated depending on where you live. For the time being, technology is such that there are far more options for life with a gas-operated combustion engine than with an electric engine, though that is changing in places.

The nature of the disaster dictates how you respond to it. A severe natural disaster might devastate an area for weeks or months. As of writing, August 16 2025, parts of the Appalachian mountains have still yet to recover from the catastrophic flooding that struck in 2024, nearly a year later. There are also man-made disasters such as war; Ukrainians near the frontline with Russia may have evacuated numerous times over the past years, or even longer ago. In maneuver warfare, one might have little or no notice to evacuate — I spoke several months ago with a family that evacuated Bucha as the sound of fighting reached them from nearby Hostomel airport. Most of the people they knew who stayed were murdered by the Russians.

The choice to stay in a place is a difficult one, and exists on a knife’s edge. That family made it out before the Russians arrived — with minutes (not hours) to spare. An interpreter of mine in Afghanistan wasn’t as lucky. He stayed put with his family, and after the government fell was murdered by unknown assailants. After a journey of years through a Pakistani refugee camp, his family made it to the U.S. Whether they will be allowed to stay here is another question.

So what additional equipment should be brought with one if one is evacuating oneself and one’s family?

-a tier-two backpack’s worth of food, season-appropriate clothes, and equipment per person.

-Three weeks of food (a Costco run’s worth) to supplement what’s in each backpack. Focus on canned goods and rice, or MREs if you can afford them.

-instead of giving each person a hatchet, one person should have a hatchet.

-An axe for splitting wood

-A crowbar

-sledgehammer and wedge

-hammer and box of nails

-bottle of ibuprofen

-portable gas generator. The Honda EU2200i is the consensus pick for powering basic necessities briefly for a month, and goes for about $1100.

-3 full five-gallon gas cans

-Seven gallons of water per adult, five gallons per child. That’s 14 for two people, 24 for a conventional family of four. Hard to pack in gallon containers; easier in 5 gallon containers or larger. Expect to begin refilling this stock ASAP. As mentioned earlier, potable water will be one of your biggest ongoing struggles.

-Soap

-Dishes and utensils

-sponges

-one towel per person

-A rifle or shotgun with a box of ammunition (in addition to the pistol)

Food, water, and fuel. Those are the basics. One can effectively make fuel to heat oneself and to melt water with an axe (by chopping firewood). One can procure water from one’s surroundings — easily or less easily depending on where you are, and where you plan to go. With enough food for the essentials, and knowledge of one’s surroundings, it may be possible to add forage to one’s diet.

You’ll have enough food and supplies to survive for a month, and depending on how far greater mobility with a vehicle. The more austere the environment, the harder it will be to survive, even with equipment. Ideally the place you choose will have supplies sufficient to provision you and your mode of transport — close to a fresh body of water (lake, river), and close to fuel in the form of gas or electricity (airport, highway rest stop, rural town or small city). Think through not only what you’ll need, but how to get more of what you need.

One should begin planning where to go and understanding the effort required to get there on the first day one leaves the site of the disaster.

At some point I will write a followup piece to this, covering how to respond to a disaster by remaining in place where and when feasible. But the effort of writing this has exhausted me.