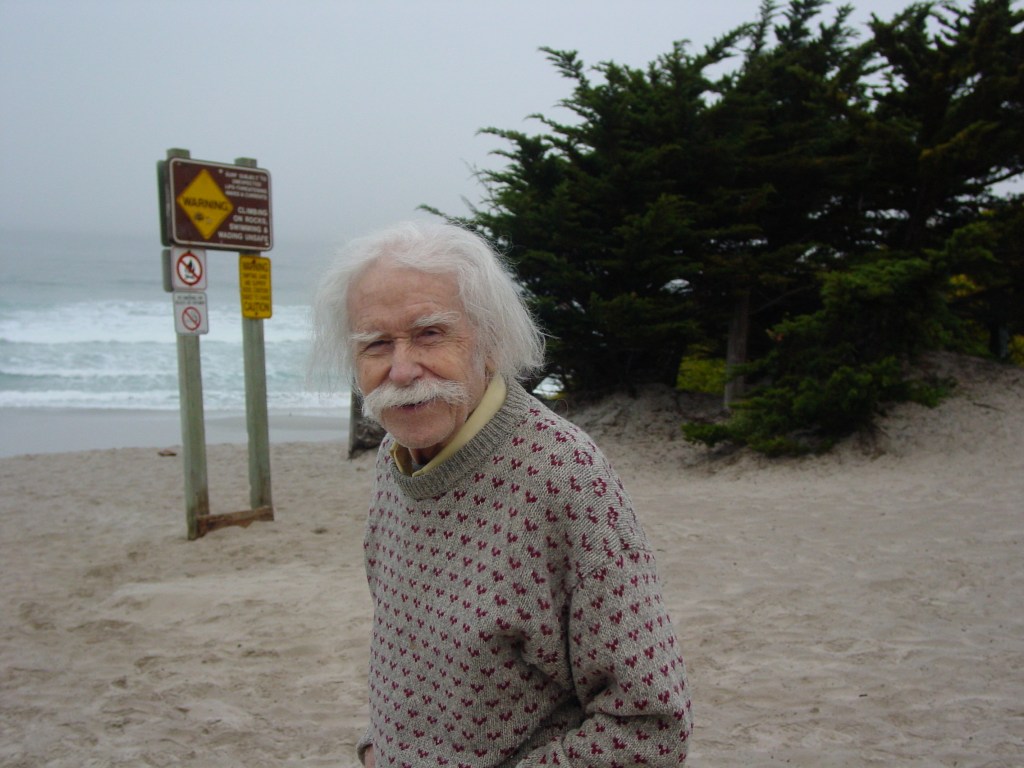

One of my favorite memories of my father’s father — my grandfather, Wes Bonenberger — was the trips we’d take together to different cities; Los Angeles, New York, Boston, San Francisco. His favorite was San Francisco. He loved the look of the city, the way the buildings lay on the land and hugged the rolling hills. He’d talk with me about architects he admired — Frank Lloyd Wright, for whom he’d worked as a draftsman early in his career (only job he’d ever been fired from, he’d say), and Frank Gehry, with whom he’d attended architecture school and hung out at USC in the 1950s.

My grandfather didn’t find it difficult to meet people, but he didn’t have many close friends. He was very picky about the people he opened up with. I could say this was a legacy of the McCarthy trials, when people in his social circle were smeared as communists and lost their careers, but I think it was always part of his character. People saw him as quirky. He had a deeply cynical sense of humor, and was thoroughly anti-authoritarian, but at his heart was an idealist who loved the little guy. He was the little guy! A lower middle class kid with a knack for designing and fixing things, who after getting out of the Army following WWII went to USC on the GI Bill.

When we’d walk through cities, Wes would talk about architecture, try (and usually fail) to impart some wisdom to me, and often end up discussing contemporaries. Gehry’s was a name that often came up — one of his close friends at architecture school — a fellow iconoclast, someone who found the architectural mainstream in 1950s America not just stale, but horrifying.

For this reason I’ve always looked at Gehry’s projects with interest; not as someone with deep aesthetic appreciation for his work or what went into it, but for the larger project of disruption and complication, of which he was an enthusiastic and deliberate part.

Farewell to the last contemporary living connection to my grandfather I’m aware of — farewell to Frank Gehry.